by Hamish Bowles

Photographed by Norman Jean Roy

Although I have lived in Manhattan since 1992, for the better part of two decades I have remained in blissful oblivion of all matters sportif. Of American football, baseball, and basketball I knew nothing. Until very recently I had absolutely no idea what the Super Bowl was, although it conjured up images of something perfectly lovely from Steuben.

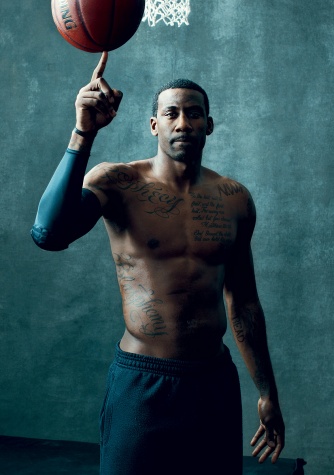

But in the midst of applying for American citizenship, of finally attempting to get my presidents in a row, I felt it incumbent upon myself to explore the national psyche in every way. So when the idea was mooted that I should shoot hoops with Amar’e Stoudemire, 28-year-old basketball deity and savior of the New York Knicks, I thought I should give it a whirl.

Click here for an exclusive video of Hamish Bowles’s training session with Amar’e Stoudemire.

Actually, I had no idea what shooting hoops was or were. I thought dunking was something you did with a beignet and a cup of steaming coffee. I wasn’t exactly sure what a Knick was.

I have had a complicated relationship with the world of sports. At the hour of my birth, my ecstatic father cradled the mewling marzipan-pink bundle in his arms and uttered the immortal words “He’s got footballer’s knees.” But Dad’s words rang like a witch’s curse through my infancy and childhood as I first crawled, then toddled, then walked, then ran away from every manner of ball—and their number was legion. Luckily a baby sister soon arrived who, from her first tentative steps, proved able to bend it like Beckham. But while her relationship with sports blossomed into a love match, mine progressed swiftly to messy divorce due to mutual incompatibility.

I have had a complicated relationship with the world of sports. At the hour of my birth, my ecstatic father cradled the mewling marzipan-pink bundle in his arms and uttered the immortal words “He’s got footballer’s knees.” But Dad’s words rang like a witch’s curse through my infancy and childhood as I first crawled, then toddled, then walked, then ran away from every manner of ball—and their number was legion. Luckily a baby sister soon arrived who, from her first tentative steps, proved able to bend it like Beckham. But while her relationship with sports blossomed into a love match, mine progressed swiftly to messy divorce due to mutual incompatibility.

For reasons that baffle me still, my high school sports coaches put me in the first division of the rugby, cricket, and soccer teams. My instinct for self-preservation led to performances that generally involved running as far and as fast away from the ball as was humanly possible (and I could certainly run), so I was more or less instantly demoted, and my subsequent appearances on the emerald or muddied field were generally heralded by the sports master’s utterance of the sonorous moniker “Butterfingers” or, in moments of extreme exasperation, “Fairy Butterfingers.” That was the last of my sports education.

Until now. I met Amar’e at the Tommy Hilfiger show in Lincoln Center last fall; his fashion instincts are remarkably honed, and he has plans to launch a clothing line of his own. “When you put your fashion on—you know, your tailor-made suits or bow ties and fedoras—you feel like you’re swagger,” he says. “You feel elegant and rich.” Basketball players have their nicknames. STAT, for “standing tall and talented,” is Amar’e’s apt one, and at six feet ten he is practically a foot taller than I am. “Basketball, man, it is a land of giants,” he tells me (I was later astonished to discover that even he seems dwarfed by his teammate Timofey Mozgov, who is a Brobdingnagian seven feet one). As a result it was not always easy to catch everything he said, as his basso-profundo voice and his carefully measured thoughts literally drifted far over my head.

Amar’e’s five-year Knicks contract is worth a little shy of $100 million, and the endorsements that inflate that sum seem destined to grow ever more substantial. But if he has found a pot of gold at the end of his rainbow—the 2010 Bentley convertible he drives to training or the Maybach 62 S (with the extra legroom and the buttery-soft interior, as luxe and cosseting as a private plane) in which he is driven; the penthouse in the Meatpacking District with its own recording studio and barbershop—the journey there has not been an easy one. He had a hardscrabble childhood. His inspirational father, Hazell, who owned a lawn-maintenance company, died when Amar’e was twelve, and his revered, powerful mother, Carrie, was in and out of the Florida penitentiary system, creating a life situation that in some ways defeated his elder brother, Hazell, Jr., once a promising basketball player himself, and their half-brother Marwan; both have spent time in prison. Amar’e was buffeted between six high schools. Faith provided one succor, sports another. “I grew up playing football and baseball,” Amar’e tells me. Amazingly, he didn’t start playing organized basketball until he was fourteen. However, he clearly had a preternatural aptitude for it; four years later he was drafted by the Phoenix Suns. In 2003 he was the first player fresh from high school to be named NBA’s Rookie of the Year (“I was like, ‘I’m here, man!’ ” he recalls).

The charismatic Knicks assistant coach Phil Weber, who put me through my paces, has worked with Amar’e for eight years. “He was kind of a blank slate when we got him in Phoenix,” says Weber, who moved to the Knicks two years before Amar’e. “The one thing about him was how fast he was able to learn. He would pick up on little subtleties.”

In 2010, after eight years with Phoenix, Amar’e’s contract expired, and he became an unrestricted free agent. That season, the contracts of some of the best players in the NBA were up for renewal. Phoenix kept Steve Nash, and LeBron James famously snubbed the Knicks (among other clamoring teams) to join the Miami Heat. Manhattan practiced the art of the hard sell on Amar’e—it was longtime Knicks fan Spike Lee who produced the video extolling the city’s virtues. But if Amar’e was considered something of a consolation prize for the Knicks, who had suffered nine straight losing seasons, his subsequent performance has roundly vindicated the choice. “He has shown his leadership,” says Coach Phil, noting that in practice Amar’e is often the first and last off court. Until a toe injury briefly sidelined him in February, he had played in 52 consecutive games, with a scoring average of 26.3 points per game, and generated a degree of excitement not seen for more than fifteen years and since the glory days of such players as Ewing, Frazier, Bradley, Reed, and DeBusschere. “I’m more comfortable leading now,” says Amar’e, who has been honing his skills by readingThe Art of War, the sixth-century Chinese military text consulted by both Mao Zedong and Napoleon.

So it was with no small degree of trepidation that I set off on the hour-plus drive upstate to the Knicks Training Center on a chill winter’s day for a practical initiation into Amar’e’s world. “There’re a lot of rules to basketball,” Amar’e tells me in a masterpiece of understatement. I have attempted to wade through the NBA rule book, fiendish refinements on the guidelines first established by Dr. James Naismith in 1891, but soon proved inadequate to the task.

So as not to make an abject fool of myself on the court, I had also embarked on a fitness regimen at the Equinox gym, where trainer Frank Salzone had put me through some intense, basketball-specific workouts, focusing on “speed, agility, endurance, reaction, and power.

“When I first met you, you did not have much muscle mass,” remembered Salzone, who showed me a poolside shot of himself that seemed to feature him clasping what looked like an armadillo to his midriff but proved, maddeningly, to be his midriff. With this inspiration in mind I endured a challenging series of squats, curls, crunches, Romanian dead lifts, planks, and (my personal favorite) the curtsy lunge, which incorporated a panoply of instruments of torture—medicine balls, resistance bands, agility ladders, hurdles, cones, reaction balls, and battle ropes among them. I started to see some gratifying changes, and also felt that my sweaty exposure to a legion of buff West Village fashionistas might somewhat inure me to the inevitable humiliations to follow.

Over breakfast at the training center, Amar’e explains his own daily routine. He is eating a Papa Bear bowl of oatmeal with rashers of turkey bacon on top (although he notes that if he breakfasts at home, his chef may prepare salmon cakes and eggs Benedict). Breakfast is followed by a rigorous assessment. “You let them know what’s hurting, what’s not hurting,” explains Amar’e, who had microfracture surgery on his left knee in 2005 and arthroscopic on his right a year later, and whose physical well-being is evidently of primary importance to the Knicks. “After a long week of games, you’ll have a lot of bumps and bruises, and you can be extremely sore at times,” Amar’e continues, “so they’ll massage it out.” This routine is followed by time in the weight room and a warm-up of bikes, balance pad, and lunges. “Then you get into your heavier lifts,” says Amar’e. “You start lifting 300 pounds. With legs.” My stomach begins to curdle. “Then it starts to get a little hectic and hard. There’s a lot of maintenance.” Practice can then run to two hours.

As Amar’e sets off to begin that dizzying program, I watch Vogue’s former intern Sean Avery cut up some ice during a New York Rangers practice (the hockey team shares the facility), and then head into the basketball courts to watch the Knicks’ training session, under the aegis of head coach Mike D’Antoni and four assistant coaches. The warm-up exercises are intense, but happily there is a moment of light relief when fourteen guys are lined up by their physiotherapist and instructed to kick their legs stridently to left and right, followed by something resembling a soft-shoe shuffle. Moving toward me in more or less perfect synchronicity, they look like the world’s most improbable cast of A Chorus Linerehearsing their moves for a rousing rendition of “One singular sensation.”

When they start to practice, the players’ speed and their kinetic movements provide a sudden flashback to the Hanna-Barbera Harlem Globetrottersanimated cartoon of my childhood, with its rubber-limbed players with quirky nicknames like Meadowlark and Geese. I am struck by the hypnotic elegance of the repetitive gestures. “It’s like dance steps,” Coach Phil tells me later, and the combination of grace and athleticism is breathtaking.

Fifteen minutes into practice, I am completely drained and exhausted—and I’m merely sitting and watching it. Trepidation melts into white-knuckle fear. Then it is over, the sports media flood onto the court, and Amar’e has a dozen microphones and tape recorders in his face.

Suddenly there is an echoing emptiness, and I am totally alone in the vast white hall. I have changed into my Knicks uniform. “When you put your uniform on, you feel more dominant,” Amar’e tells me. “You feel ready to take over, have a great game.” I wasn’t quite sure about the ultramarine, orange, and white mélange, but when I put it on for the first time it’s giving me eighties Stephen Sprouse (although NBA regulations stipulate that the shirt is tucked inside the shorts, rather than worn Teri Toye–minidress style).

Coach Phil appears and is all business. “We are going to start with ball handling,” he says. “When you feel comfortable with the ball, everything else opens up. We’ll be shooting a layup. Dribbling. These players have the ball on a string—it’s part of their body.” Unfortunately, the ball seems to be repelled rather than attracted by my hand. I spend more time collecting it from the farthest reaches of the court than actually dribbling it.

“One of the most important attributes is quickness,” explains Coach Phil patiently. “Like a magician you can become four times quicker with low, hard dribbles.” I try this, and remarkably it’s true—I can control the ball and more or less move it from point A to point B as directed. Getting the ball to describe a figure eight around my legs as the players did so effortlessly in practice is, however, a stretch too far. Coach Phil is indulgent. “Practice doesn’t make perfect!” he yells. “Perfect practice makes perfect!”

We are five minutes in, and I am blessing Frank for pushing me to go the extra mile in our workout sessions—three months ago they would have had to take me out on a stretcher at this point. Coach Phil positions my arm and hand into the craning swan-neck position, I balance the unwieldly ball on my outstretched palm, and I fire away toward the net. Over and over and over. “Physical balance, mental balance. Repetition,” says Coach. “Think of it as building a steel cable.” If I fail to position my upper arm to forearm at a perfect 45-degree angle, or hold the ball with anything other than the pads of my fingers, he makes the eh-uhdamp-squib sound effect. “You just broke six strands of that cable!” he says, sighing, and sure enough the ball goes wide of the mark. Miraculously, when I follow his routine to the letter, the ball describes a spinning arc and lands in the net. Coach Phil’s piercing blue eyes take on a sparkle that I fondly imagine Professor Higgins’s might have done when Eliza caught her first H.

“Take every shot like you know you are going to nail it!” he shouts. “Confidence equals contract!” I don’t know what curious magic is happening here, but I am on some kind of a roll and make six baskets in rapid succession. “Way to go!” says Coach. “Awesome! You nailed it!”

Butterfingers?

January 14 is my first basketball game. The Knicks are playing the Sacramento Kings, ranked at the bottom of the league. I’ve been given Amar’e’s seats and have attempted to approximate the team colors with a teal Balenciaga twinset and an orange Charvet tie. I realize the purple socks are a mistake as soon as I see the Kings’ colors, and I discreetly fold down my trouser cuffs. But if I am worried that I am overdressed, my sartorial fears are swiftly allayed by the appearance of one Walter “Clyde” Frazier, who led the Knicks to NBA championships in 1970 and 1973 and is now a commentator for the MSG Network. The dashing Frazier is channeling Harlem Renaissance dandy in Cuban heels, matching pink shirt, tie, and pocket square, and a fob chain. Apparently he once appeared in a cow-print jacket, made after he had been inspired to repurpose an upholstery fabric he was using for home decorating.

There is a giddy, carnival atmosphere. Trees of cotton candy wobble through the crowds that include dozens of children and even toddlers dressed in Stoudemire shirts. “Amareeeeeeeee Stoudemire,” says the announcer, and the crowd erupts. “It’s game time. . . . Let’s play ball!”

Everyone is moving so fast on the court that the game is almost illusory. Amar’e is like a pantomime magician, with feints and sleight of hand and improbable arm extensions and effortless swinging from the rim of the hoop. (I tried this; it hurts like hell.) When he leaps, he achieves balletic elevation and grace. And he moves likes greased lightning; as I work my way through a foot-long hot dog, I miss his ninth basket altogether, he dunks so fast.

A Bollywood moviemaker who has been following the Knicks for seven years is sitting behind me. “I am finally vindicated,” he says, exultant. “Stoudemire’s definitely changed the whole dynamic of the game.”

When the Kings take their first free throw, the bank of Knicks fans behind the basket brings out a surreal forest of frantically clickety-clacking orange slapsticks. I don’t know what effect it’s having on the players, but it’s certainly doing my head in. But then, I am on beer number two, and the Garden is swaying before me, and I am having visions of the menacing convention-hall scene in The Manchurian Candidate.

The game is not going well. The Knicks’ offense seems listless, and they trail the Kings by fourteen points at the start of the fourth quarter. When it becomes clear that no late rally is at hand, the fans start leaving in droves. This is so odd to me after following soccer, in which something transformational can happen in the last second of a match.

In the changing room there is the general air of deflation following a defeat (final score: Kings 93, Knicks 83). The players hug the tiny figure of Chrysa Chin, an ex–social worker who ministers to their spiritual well-being and emits a potent aura of maternal kindliness.

Amar’e doesn’t stay long. He strips off his shirt to reveal a torso as improbably chiseled and triangular as a Knossos statue and, emblazoned in beautiful copperplate on his back, the words STILL I RISE—the title of Tupac Shakur’s powerful rap song. Then he changes into above-the-ankle black jeans, blue suede Nike Air trainers with white and gold accents, a black tee, and a Nike New York Destroyer bomber jacket. To this Fonzian ensemble he adds the insouciant flourish of a chain-link necklace, each link composed of a different tone of pavé diamonds. Although it strikes me as something Lily Safra might choose for lunch at Harry’s Bar, naturally it looks the essence of hip manliness on Amar’e.

Two weeks later the Day of Judgment has arrived—it is time to pit my newly acquired skills against the master’s—and my nerves are in tatters. I keep repeating the mantra: I am going to go out there and have fun! But I still feel like a condemned man.

“He’s been practicing, right?” Amar’e asks Coach Phil. “If we had a test on designing, I’d lose, no question. But right now he’s on my turf, and it’s capital punishment. I’m going to go out there and kill him!”

Coach and Amar’e are looking at a Dead Man Walking.

The Sprousian uniform is, as Amar’e promised, oddly empowering. “You are ready to go!” says Coach Phil, cracking up at the spectacle. “You got it going on. That is the look. Stylin’ and profilin’! How would you rate yourself right now?”

“On fear factor, I’d say pretty high.”

Coach Phil tries to instill appropriately macho attitude. “Act like you’re as mad as you’ve even been in your life,” he tells me. “You cannot smile. I repeat, do not smile. You tell him to go to the top of the key, OK? You say, ‘Your ball!’ with an attitude. I want you to walk straight up to him, get down in a defensive stance like we talked about, and put the ball right in his chest and say, ‘Go for it.’ And then the rest is up to you.”

“He’s twice my size,” I protest. “I can’t do that.”

Coach is not hearing this. “Wheelin’ and dealin,’ ” he enjoins. “You will be onfire.”

I am grateful for his charity, but although I feel the flames licking at my feet, the sensation is more Joan of Arc than rocket propulsion. I will be embers within moments. “Oh, he’s just a big teddy bear,” says Coach Phil reassuringly. “Don’t even worry about six-foot-ten Amar’e, who can jump 40 inches off the ground. Don’t even worry about that wingspan that can put that ball into another galaxy. Don’t even worry about it!” That smile evaporates soon enough.

“We’re going to play one-on-one to ten,” explains Amar’e. “If you score, you keep the ball. If you don’t score . . . you just don’t score. First to ten wins.”

“I have to make ten of those?” I ask, jaw agape. “How long have you got?”

“OK, let’s make it fair. Let’s make it ten to one. I’ve got to score ten; you’ve got to score one.”

“Get into him! Get into him!” screams Coach Phil. But there are two fundamentals that I have not accounted for. The first is this: If you block Amar’e Stoudemire, he will knock you out of the way. Picture a wisp of thistledown caught in the eye of a perfect storm, and you get the idea. The second is this: The ball is moving so fast that you cannot see it (as is Amar’e, who generally wears out three pairs of his size 16 shoes per game). In my peripheral vision there is a blur of orange. The next thing, Amar’e has one hand on the ring and is executing a slam dunk with the other.

What seems like moments later we are at six-zip, Amar’e calls time out, and I convene with Coach. “If I score now, game’s over,” explains Amar’e.

“Do not let him get to the basket,” says Coach hopefully. “Stay in front! Now go get it; go get the rebound!” By the time I get my first rebound, Amar’e has nine points. This does not sound good. I am spinning around like a poltergeist and shaking with exhaustion. Frank’s workouts could be grueling, but at least there were water breaks between the supersets. This is pitiless. Amar’e’s physicality is superhuman.

“There’s a little bit of a height disadvantage, a little bit of an athleticism disadvantage,” says Coach Phil. “But you were up against him. You were very active.”

“Totally in the grill; I couldn’t get past it,” Amar’e chimes in, which frankly is little short of saintly of him.

Game over, we move on to some techniques.

“When you’re shooting, it’s hard to shoot with the palm of your hand,” says Amar’e. “You have to use your fingers. It just rolls off.” Then he holds the ball from above.“It helps when you dunk,” he explains. This proves physically impossible for me to do—I can barely hold the ball from the bottom. I show Amar’e that he could cup my entire hand in his palm. “Night and day,” he concedes.

Amar’e then brings out a padded silhouette figure designed to stand in for a member of the opposing team. “In the NBA there is a guy guarding you, and you really have to try shooting over him,” he says. This is difficult enough, but when he starts waving the figure about it’s nigh impossible. I am a sopping mess.

“I see you can perform under pressure,” says Amar’e sweetly. “Let me show you what I would do.” And so saying he executes a perfect Nijinsky leap, soaring high above the figure I am frantically flailing above my head. Naturally he dunks the wretched ball right in. Then for good measure he does the same thing—only backward.

“Now you try,” he says.

“Do you have a stepladder?” I ask.

Courtesy of Vogue Magazine, please read the complete article here.